Revisiting History: Florence Price – The Gifted Outsider

Article by Jacqueline Leung (MGBH)

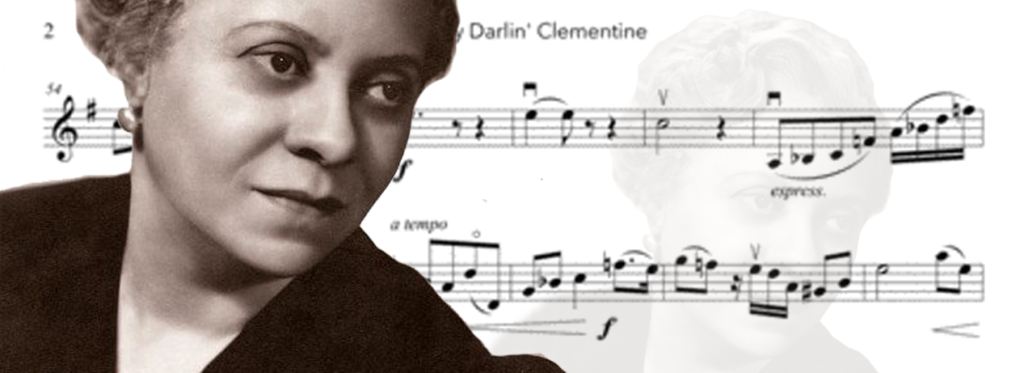

In recent years, Florence Price (OBM), described as “something of a mystery (1),” is beginning to emerge as an American composer of important contributions. One can gather from many online sources that Price was the first African American female composer to have a major symphonic work performed by a major American orchestra – the Chicago Symphony. Therefore, at a first glance, it appears that Price achieved major success in her career by reaching this important milestone. However, upon closer examination, once can see that her musical path was paved with obstacles and struggles.

Please, consider donating a small amount to the author to express your appreciation.

Florence Price, née Florence Beatrice Smith was born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1887 to parents of French, Spanish, English, Indian, and “Negro” heritage (2). Despite her white bloodline, her African roots inadvertently “tainted” her chances of substantial success in the classical music world. It may be argued that she had already achieved success with the performance by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, however, many have ignored the fact that the performance took place on World Fair Day and not a regular season series concert, hence, her work still hovered on the periphery of the dominant white world. Towards the end of her life, she wrote to a friend in Atlanta after having struggled to secure a concert engagement for 20 years, “I have finally learned that the successful ones amongst us are usually recognized by us only after the white man has put his stamp of approval on us (3).”

Price was first taught the piano by her mother and had her first composition published at age 11. Her musical talent was recognized early. Growing up in a household where the cream of travelling African American artists and intelligentsia often frequented, she had broad exposure to the arts world since childhood. World travelling pianist Blind Boone (OBM) was once a houseguest of the Smiths and reportedly showed interest in hearing Florence play. Florence continued her tertiary education at the New England Conservatory in Boston, Massachusetts, majoring in piano and organ as well as studying composition. She was one of the very few students with a double major and graduated with honors in 1906. In her year, a mere 58 students out of 2000 graduated, and she was the only student who pursued two degrees. At NEC, she was selected to play at various important concerts, and the repertoire she performed showcased her as a highly skilled organist and pianist. However, after graduation she did not stay in Boston to pursue a performing career, but returned to the South where she became a teacher of music. Later, between 1910-1912, she headed the Music Department of Clark University in Atlanta. In her personal life, she met her husband Thomas J. Price (OBM), an attorney with a career of promise.

After a few years of settling in the South and raising a family with two daughters in Little Rock, she started experiencing escalated racial tension. The White American Music Teachers Association turned down her applications to join the society. With lynching and segregation laws being implemented, the movement evoked a massive ‘migration,’ some 6 million African Americans emigrated north. As the racial segregation situation worsened, the Prices moved the whole family to Chicago to escape from the brutal situation down south. In Chicago, Florence’s career was able to flourish. She mingled among the most gifted and influential African American social circles. The support led to more compositions despite leading a busy life. Invitations flowed in, including lectures on rare instruments for the Chicago Music Association. However, Florence’s husband suffered from the Great Depression and lost many clients. His law firm and client lists dwindled, and facing increasing financial difficulties, he became abusive towards Florence. Inevitably, she had to divorce him to lead a single mother life with her two daughters. Being the sole breadwinner of the family meant that she had to work as much as possible to provide for the household. Her various jobs included being the organist for silent film screenings. It is important to note that this was a position tailored for white musicians, in a theatre with predominantly white audiences. Thus, Florence must have been hired for her skills. Other jobs included running a large private piano studio at home and publishing her own teaching pieces to supplement her income as well as composing songs for radio under a pen name.

During a period when she broke her foot, she was forced to stay at home and rest. With more time on her hands, she devoted time to compose her first symphony. Despite her injury, the time she had for composing this large-scale work proved to be a fortuitous turning point in her career. She entered two compositions – her Symphony in E minor and Piano Sonata – into a competition hosted by the Wanamaker Foundation. Out of a total of $1, 000 awards, her Symphony won first prize of $500 and the Piano Sonata won the 3rd prize of $250. This very success garnered attention of Frederic Stock (OBM), the conductor of the Chicago Symphony at the time, who thought very highly of her work and decided to program her symphony. In 1940, following the accolades she received for her composition at this performance, she was inducted into the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers. Aside from composing large-scale works such as symphonies, sonatas, and concertos, Price was an avid arranger of spirituals. Delving into her heritage for musical inspiration, she utilized elements of African American music in her compositions. Her 3rd Symphony, for example, is written in the Juba dance style, of West African heritage. Not only did Price arrange spirituals, she also incorporated them into her compositions. The second movement of her piano sonata for example, is a poignant movement and uses elements of spirituals as a basis of the musical language. It is a known fact that Antonin Dvořák (OBM) recognized the importance of incorporating ‘folk’ or ‘common people’ elements into Western classical art music, and he once predicted that spirituals would become the basis of American compositions.

Leading African American musicians including Marian Anderson (OBM) and Leontyne Price (OBM) performed her works in public concerts, during national events, and on radio. Her Piano Concerto gained the support of Frederic Stock again, who conducted the premiere of her piano concerto with her student and Margaret Bond (OBM) as a soloist. In the 1950s, Sir John Barbirolli (OBM), director of the Halle Orchestra in England, asked her to write a work made up of spirituals, which is a testament of how well- regarded her compositions were. Other ensembles, which performed her other works included the U.S. Marine Band, the Pittsburg Symphony, the New York City Symphonic Band, and the Michigan Symphony. For a period, she wrote using the pseudo name of Vee Jay, which, perhaps, gives us a hint of her fear of rejection due to her ethnical heritage if her real name is recognized. A particular work, At the Cotton Gin was published by Schirmer (OBM). A thorough examination of her correspondence reveals, however, that while she did receive praise for some of her works, it was at times difficult to have all of her submitted compositions published. Having received her formal musical education in Boston, she especially lamented being rejected by Serge Koussevitzky (OBM), the music director of the Boston Symphony, who turned a blind eye to her plead to look at her scores. She wrote, “I’m a woman and I have Negro blood in my veins,” (5) and she understood that race and gender were her two ‘handicaps’, limiting her path to wider success.

Despite rejection by some American organizations, she did receive recognition from key figures such as Eleanor Roosevelt (OBM), who recognized her contribution in 1933 after attending the World’s Fair concert in Chicago. In 1953, she received a letter from Clayton F. Summy Co. music publishers, which referred to her works as ‘attractive’ and that they ‘hope to see more of [her] compositions. Valter Poole (OBM), conductor of the Michigan Symphony Orchestra was “very interested and quite anxious to do something from [her] pen.” She appeared at the NANM (National Association of Negro Musicians) Convention in Chicago, and attendees were referred to as the “Finest Music Talent In the Country.” Rae Linda Brown (OBM), a scholar of Price’s work, remarked in Drew Magazine, 2011 that Price was “a piece of African-American history, a very important piece of history.”

To this day, Florence Price is far from being a household name. Along with her counterpart, the African American composer William Grant Still (OBM), also from Little Rock, their works are still awaiting to be widely recognized. Price’s lively piano teaching pieces for children with animated titles such as ‘Tip-Toe To the Cookie Jar,’ ‘Pop Corn,’ ‘Washing Machine,’ and ‘Criss Cross’ would appeal to children who could relate the music to their everyday lives. Many of these pieces are still relatively unknown in piano pedagogical circles. Among these, a short teaching piece, “The Goblin and the Mosquito”, written for the elementary level pianist is a great study of hand coordination, yet containing varied thematic material. Works available online are few and far between and to date, and many of these compositions are still unpublished. Her Piano Concerto, with the complete score lost since the 1940s, was reconstructed in 2011 by composer Trevor Weston (MGBH) with a commission from Center for Black Music Research. It received a premiere by Dr. Karen Walwyn (MGBH), a devotee of Price’s music. Yet, her compositions including her violin concertos and numerous other works, would be a very welcome addition to the American art music repertoire.

The compositions of Florence Price deserve much closer attention and recognition from classical music circles. The story of her life is a courageous and heroic one, with her having upheld herself as a strong willed, capable, and independent woman living in challenging times of the history of the United States. Traditionally, female composers have always been outnumbered by male composers, and being a female African American composer is a rarity. Her efforts and perseverance to break down the invisible walls, inch by inch, are still very much relevant today.

References:

(1) “Price, Florence Beatrice Smith (1887-1953) | The Black Past: Remembered and Reclaimed.” www.blackpast.org/aah/price-florence-beatrice-smith-1887-1953.

(2) Gordon, Ashleigh. “The Life and Music of Florence Price: An Interview with Rae Linda Brown.” AAIHS, www.aaihs.org/the-life-and-music-of-florence-price-an-interview-with-rae-linda-brown/. Accessed 14 Aug. 2017.

(3) Hann, Christopher. “The Lost Concerto | Drew Today | Drew University.” Drew Today, 2011, www.drew.edu/news/2016/04/21/the-lost-concerto-2. Accessed 14 Aug. 2017.

Enjoyed the article? Please, consider donating a small amount to the author to express your appreciation.

About The Author:

Jacqueline Leung is a Hong Kong based concert pianist and educator. She was trained at the Royal Academy of Music in London and Texas Christian University in Fort Worth. She has performed on four continents and is in demand as a solo and chamber musician, lecturer and adjudicator. Alongside music, her passions include traveling and cooking. She also holds a MA in Comparative Literature from the University of Hong Kong. She has recently been appointed as Senior Lecturer of Music (Piano) at United International College, China.

[1] Christopher Hann, Drew Magazine 2011

[2] Handwritten document on a form from the University of Arkansas Special Collections archives

[3] WQXR Radio Feature by Terrance McKnight

[4] Great Divide at the Concert Hall, New York Times, Aug 2014

Piano Performer Magazine

Piano Performer Magazine