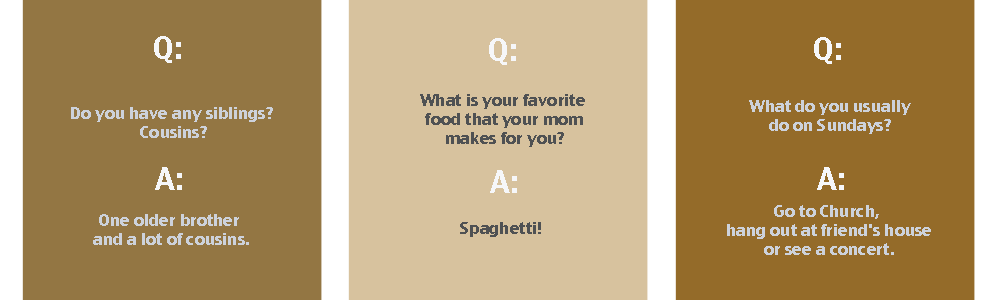

Interview by Peter Robinson (MGBH)

When one studies piano from childhood and puts effort to excel in this craft, it stays with him (or, in our case – with her) for life, regardless of the occupation she chooses as an adult. Many times an opportunity of continuing with piano professionally is foregone due to limited career choices as a pianist.

Nevertheless, once a pianist – always a pianist. Even if one becomes a Secretary of State.

Peter Robinson (MGBH), (PR): You have given a very substantial portion of your life to this endeavor. Why?

Condoleezza Rice (MGBH), (CR) : Classical music is one of the highest forms of the arts that human beings have ever achieved. If you look at the complexity of what these great composers were able to do, you wonder how the mind was able to create this. And we have to stay connected to this marvelous music. We have to stay connected to this heritage of this highest art form. And I understand that it’s not “popular,” but not everything is “popular.” We still have to preserve it, we have to perform it, we have to play it, we have to try to introduce our children to it and one of the ways that we do that is to make certain that we keep the arts in the schools and we keep the arts in a sense of a broad education. I know there is a lot of talk these days about stem and technology, but there is nothing more human in terms of what these composers were able to do.

Classical music is one of the highest forms of the arts that human beings have ever achieved.

PR: Take me to the Rice household, back in Alabama. Who persuaded you to start playing?

CR: Well, I was very fortunate. I come from a musical family. My mother (OBM), my grandmother (OBM), and my great grandmother (OBM) were all pianists. And my mother was a wonderful pianist and a church organist. And my grandmother was actually classically trained… in the South, right? In the early 1920s…

Little Condoleezza playing piano

Little Condoleezza playing piano

PR: How did that happen? That’s extraordinary!

CR: It’s kind of a mystery to me, too. She was the daughter of an African-American episcopal preacher or bishop, actually, very high up in the church. And he somehow found this Viennese master to teach his daughter piano. And, so, she learned to play very young. She taught piano lessons, and while my parents were teaching school, I would stay at her house from age 3,4, 5, until I could go to school. And I wanted to play. Her kids would come over to have a piano lesson. She charged 25 cents a lesson. And at the end of it, I would go to the piano, and I would bang at the piano. And my grandmother said, finally, “Angelina (my mother’s name), let me teach her how to play. I think she wants to learn to play. “ I was three. And my mother said, “Don’t you think she is a little young?” And my grandmother said, “Well, we are gonna find out.” And so, I, actually, never remembered learning to read music, which I do think it’s an advantage, because reading music, particularly reading piano music, is quite complex. You have two hands, you have clefs. They are moving this way and that way simultaneously. And, by the way, if people want yet another reason to play the piano…. I played Schumann (OBM) with the Omaha symphony a couple of years ago, and I realized I had to memorize the score because you can’t really play with the score. And a few weeks later I was talking to the head of neurology here at Stanford, and he said, “You memorized that score?” And I said, “Yes.” And he said, “You have no idea what you’ve done for your neuroplasticity!” So, for all of us that are looking for agelessness, learn to play the piano. But I started very, very young.

She charged 25 cents a lesson. And at the end of it, I would go to the piano, and I would bang at the piano.

My parents let me learn to play the piano. And there is one great story. I said as a 4-year-old, “I need a piano.” We didn’t have one at home. We had a little organ, you know, one of those little play organs for kids. And I said, “I can’t play all the notes that I need on this little organ.” So, what my father said was, “Ok, when you learn to play What a friend we have in Jesus perfectly, we’ll buy you a piano.” My grandmother said that the next day at her house I sat there for 8 hours. I wouldn’t even have lunch. When they came back, I knew What a friend we have in Jesus perfectly. And my parents had to go out and rent a piano, ‘cause they couldn’t really afford one. But I am lucky to have been exposed to music, classical music, very early.

PR: That’s an unusual story. Even at that, a lot of kids will start fairly early and then junior high comes along. Sports kick in. They drop it. Or they go to college and drop it. Was there a moment when you knew, “This is a keeper for me. This is going to be part of my life”?

CR: Well, there was a moment when I almost dropped it. At age 10, having played by now for 6 and a half years, I went to my mother and said, “I am quitting. I am tired of playing the piano.” And my mother said, “You are not old enough or good enough to make that decision.” So, I kept playing. And when I had a chance to play this great music with George at his studio or to play with Yo-Yo Ma (MGBH) in Washington or play with the Omaha Symphony, I looked towards heavens, and I said, “Thanks, Mom, for not letting me quit.”

At the age of 10.

At the age of 10.

PR: So, you are practicing the piano while working in the White House. Practicing the piano as a Secretary of State. Now, I’d like to probe that very odd notion a little bit. You are known as a person of unusual accomplishment. That’s not subjective, anyone would agree to that. Also, as a person of unusual discipline. I think that’s generally the case. But there is nothing about the sort of “dread sense of duty” that I pick up when you talk about the piano. What were you getting out of it? Why did you make the time?

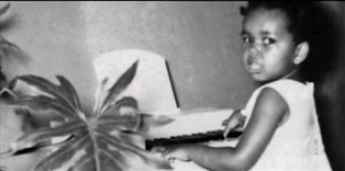

CR: Well, the first thing… because I had decided at the end of my junior year that I was about to end up playing in those department stores while people shop, perhaps, I could find something else. I’ve gone to the Aspen Music Festival and met real prodigies, and I thought, “Oh, I am really ok, but not THAT good.” And, so, I went back to college at the end of my junior year, found International Relations and decided to go that direction. And that’s why, of course, ultimately I would end up Secretary of State because I made the switch. But in-between, finishing college and going to graduate school, I played, actually, very little. I taught piano lessons to make money for graduate school because it was better than waiting tables. Only barely, but better than waiting tables. And then, I was here as Provost. And in 1993, Paul Brest (MGBH), we was then Dean of the Law School, and plays the viola, said, “You play the piano. My chamber group would like to play some music with a piano. I said, “Paul, I haven’t played serious music in years.” But I started playing a little bit with him, and I thought, “You know, if I am gonna do this, I’m gonna do it right.” And I went to George Bart (MGBH) and said, “Who is the head of the piano department?” I’d just become Provost. They said, “George Bart.” So, I called up Professor Bart, and I said, “I’d like to come see you. I want to take piano lessons.”

PR: Was there one lesson when you could tell that George was taking you seriously?

CR: Oh, from the very beginning. I played about four bars, and he’d say, “No, no, no. Wait, here. Let’s do that again . . . and think about this.” But that Brahms (OBM), the wonderful thing about this, it’s a bear of a piece for a piano. It really is. And we would work two hours – three hours at a time on this piece, ten hours a week. And in life you have to find time for things that are fulfilling for you. And for me these were in many ways the most fulfilling two or three hours of the week because… people say, “Well, it must be relaxing.” It’s not actually relaxing struggling for Brahms. It’s really hard work. But it is transporting. When you are playing, when you are practicing, nothing else can be in your head. And that was the secret also when I was a National Security Advisor, Secretary of State. Even if you are trying to relax and say, “I am just gonna sit here and read a book. I am just gonna sit here and watch a television,” your mind is spinning. When you are playing the piano, there is no room in there for anything to spin. So, it truly does get you completely away.

Condoleezza Rice playing with in a chamber group

Condoleezza Rice playing with in a chamber group

And during those 8 years in Washington, I found a chamber group I played with mostly very fine musicians who were no longer professional musicians. And they were wonderful, because they didn’t care if I am “Secretary of the Moon.” They just wanted their pianist.

It’s really hard work. But it is transporting. When you are playing, when you are practicing, nothing else can be in your head. And that was the secret also when I was a National Security Advisor, Secretary of State.

PR: So, this is a crude way of putting it, but again, I am still on this question what it did for you, what you got out of it. Did it enable you to serve as a Secretary of State better? Were you a better Secretary of State because you were playing Brahms?

CR: Absolutely. Apart keeping my balance, keeping my center during all of the troubled times, when you are Secretary of State, and you are at the top of the food chain, so to speak, you can also lose a sense of who you were and who you are and that kind of core. And music, maybe because I started so young, maybe because I associate it with my mother and my family, is the core of who I am. And in those times you have to hang on to things, the core of who you are.

PR: You’ve mentioned Brahms. And I know from reading up on you and from talking to George, that you just love Brahms. And if I may say so, Brahms seems to me an odd hill, on which to make a stand. Bach (OBM) – way in the beginning. You know what it is. It represents the whole world onto itself. Mozart (OBM) – of course. Beethoven (OBM) – of course. And then, on the other side of Brahms, you have the people who are real romantics, people who are really just … wonderful tonal experiments: Chopin (OBM), Debussy (OBM). But Brahms, Madam Secretary, is not one thing or the other. He is kind of stuck in-between this classical world where form is everything and the romantic world where it’s subjective and impressionistic. He is just stuck there. I ask you to rise to the defense of your honest Brahms.

CR: Brahms, obviously, cared a great deal about a classical form. And that’s what I love about Brahms – it’s this effort to bring back Bach or Mozart. And when you look at what he did, it’s remarkable that you can compose within that discipline.

PR: …he saw himself as a reinventor of the tradition, in part. No?

CR: Well, I think he extended that tradition. Of course, he lived in a period, in which all of this expression was possible, and in which as these modulations and harmonies were modulations and harmonies that you find even anticipated in Mozart or Beethoven, but taken to their fullest extent in Brahms. And the really interesting thing is that… he died in 1897. So, had he lived a few more years, he would have experienced the 20th century. And I find myself all the time wondering how Brahms would have experienced 1910, 19…, because he anticipates some of what you’ll see in Schoenburg, even. And Schoenburg wrote a very famous article “Brahms, The Progressive?” in which he lays claim to Brahms as someone who was already pushing the envelope. So, I, actually, see Brahms as someone who took this classical tradition, this what someone might have experienced or thought of by the time Brahms was composing, as a straight jacket. He didn’t think of it as a straight jacket. He thought of it as enabling him to push this forward and move this forward. And you look at some of the harmonic and rhythmic uses that he makes and it’s just extraordinary. Brahms is also for me passionate without being overly sentimental. And I rather like that.

PR: Ah… That’s your formula.

CR: That’s my formula.

PR: Got it. Ok, that one clicks for me. Who is your current? Is Brahms still your man?

CR: Brahms is still my man. I love a lot of composers.

I don’t know that entry needs to be easy for everything in life. Sometimes having to work at something is not a bad thing.

PR: I know that you believe in free markets. Does it shake you a little bit, does it shake your faith in free markets that the markets don’t really reward this endeavor, particularly? As they said, the classical music is 2% of the marketplace. This is nothing new. Mozart died virtually bankrupt. In a certain sense, people treated him more as a celebrity rather than showed deep appreciation of his music.

CR: Brahms, by the way, did very well thanks to the piece that he hated – Brahms’ lullabies. But markets operate on information. And sometimes information is imperfect, economists will tell you. And I think information is imperfect about what classical music can provide. And that’s why I think it is so important to introduce kids to it, it’s important to bring it into the schools, bring students here who, perhaps, don’t know it when they arrive but when they find it compelling. I just have to believe that when people really have a chance to encounter classical music, they’ll buy it.

Markets operate on information. And sometimes information is imperfect, economists will tell you. And I think information is imperfect about what classical music can provide.

PR: Ok, so, one more question along those lines. It was thought. I will put it in a passive voice. I’ll put myself in the middle of it – I thought. A lot of people thought, ten years ago, a dozen years ago, as first CDs came along, and then the Internet… Itunes, Spotify, and so forth, that we have this wonderful democratization of music. You know we are a long way from having to get dressed up in an evening gown, dinner jacket, and go to Carnegie Hall to hear classical music. You can download it at the touch of a button. And I was among those who thought, “People will find it. It’s so powerful, it’s so beautiful, and it’s so compelling.” We stand at the very beginning of an age of rebirth and interest and appreciation of this kind of music.” And it just hasn’t happened this way.

CR: Well, I’ll give you two reasons for that. One is, first of all, entry to it isn’t that easy. And I don’t know that entry needs to be easy for everything in life. Sometimes having to work at something is not a bad thing. Sometimes having to read great literature even though it’s not immediately like the plot line one finds in a half-hour sitcom. There are these great arts that take a little work sometimes …So, I think getting kids introduced to the arts in a way that allows them to access them rather than dumping it at them, is really very important. Then, secondly, I do think that we may underestimate the degree to which people go online and maybe they just listen to one piece, maybe they hear one performance. And finding way to capture that is not so easy. But I suspect that there are more people who hear this music in one way or another, maybe if it’s even in a movie theme or something. But we have to do a better job, we have to do it in the schools, we have to do it in places like this. We have to make it available. And I still think people will learn to love it.

About the Interviewer:

Peter M. Robinson is a research fellow at the Hoover Institution, where he writes about business and politics, edits Hoover’s quarterly journal, the Hoover Digest, and hosts Hoover’s video series program, Uncommon Knowledge™.

This Interview has been transcribed with permission of Hoover Institute at Stanford University.

Piano Performer Magazine

Piano Performer Magazine

Little Condoleezza playing piano

Little Condoleezza playing piano At the age of 10.

At the age of 10. Condoleezza Rice playing with in a chamber group

Condoleezza Rice playing with in a chamber group

Szigeti plays Schubert’s “The Bee”

Szigeti plays Schubert’s “The Bee”